At Monsoon, a bistro in Tehran that serves sushi, Szechwan beef, and Gouda and calamari on whole wheat toast, the fusion cuisine is an act of defiance. So are the women’s fashions—tight robes, exposed calves, headscarves that barely conceal blond and henna-colored hairstyles. The restaurant, with its rough concrete walls, red countertops, and statues of Hindu and Buddhist goddesses, looks more Manhattan than Islamic Republic.

Seated at a corner table is Elham Hassanzadeh, almost 6 feet tall, with dark eyes, thick eyebrows, and lush brown hair that overflows her hijab. Her dining companions are the middle-aged bosses of two large Iranian engineering and construction companies.

Raised in a pistachio-farming family in tradition-minded southern Iran, Hassanzadeh, 31, earned her law degree and Ph.D. in the U.K. on scholarships. She literally wrote the book on Iran’s natural gas industry since the 1979 Islamic revolution—it was published last year by Oxford University Press.

She has returned to Iran to head a consulting firm, Energy Pioneers, based in Tehran and London, that’s at the vanguard of Iran’s all-out push to lure back foreign investors after the expected lifting of sanctions in coming months. Iran is counting on Western technology and hoping to raise $100 billion in overseas financing to double its oil and gas production in the next five years. Hassanzadeh is building a business by parlaying a deep knowledge of Iran’s energy resources, close ties to government technocrats and industry leaders in Tehran, and high-level contacts at major oil companies, law firms, and investment houses in the West.

Her clients are impatient. “Foreign companies should open offices in Tehran immediately and buy shares in local companies who can be their agents and help with management,” says one of Hassanzadeh’s dinner companions, B.M. Hazrati. He’s the managing director of Arsa International Construction and head of a contractors’ trade group. “Unfortunately, they’re still looking at us like it’s 15 years ago.”

“The world has moved on,” Hassanzadeh says, dismissing the idea that Western investors, in a market glutted with oil, are ready to rush back to Tehran without examining the fine print. Lately she’s been commuting between Iran and Europe to speak at trade conferences and in meetings with Western oil executives, fund managers, bankers, and lawyers about her country’s reemergence.

Despite her age, she cultivated a wide network of industry players in Europe during her years at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. Some of these contacts may have skirted U.S. law by merely discussing business with an Iranian, so Hassanzadeh names no names as she shares what she’s learned: Significant Western involvement in Iran’s oil sector is at least 18 to 24 months away, maybe much more. Prospective partners don’t trust the project information they’re getting out of Tehran, she says, and the big banks and investment funds “still need a clear green light” from the U.S. Department of the Treasury before committing money to Iran. “For them, Iranian stability is still questioned,” she says. “What happens in two years if [reformist President Hassan] Rouhani isn’t reelected?”

The dour assessment rankles Hassanzadeh’s other guest, Mehrdad Motarjemi, managing director of Gamma, a Tehran company that recently completed Iran’s biggest natural gas production unit in the Persian Gulf, called South Pars Phase 12. “You can always make a long list of what-ifs,” says the silver-haired executive, 60, whose smile and soft voice belie a snappy disposition. “What if Donald Trump becomes the next U.S. president?”

The conversation shifts to another debate raging inside Iran’s oil industry—between those who argue that Phase 12 and other achievements during the four years of global sanctions prove Iran doesn’t need foreign help, and executives such as Motarjemi who say international technology and management expertise are indispensable. Phase 12, while hailed in Iran as a triumph of self-sufficiency, cost twice as much as it should have because of sanctions, according to Motarjemi.

“You can’t imagine how difficult it was,” he says. Banks in Dubai and Asia charged usurious rates to move Iranian money. Western suppliers labeled random components such as piping and valves “dual use”—that is, applicable in military or nuclear technology—and wouldn’t sell them to Iran. Spare parts never arrived for some critical components such as pumps; a massive compressor is still on a dock in Dubai, mired in sanctions red tape.

“I’ve seen how management functions much better when there’s a European company working beside us,” Motarjemi says over a dessert of fried mango spring rolls with coconut ice cream. “We want to forget the past hatred, whatever it was, and start all over again.”

Undeterred by this month’s flareup with sectarian rival Saudi Arabia across the Persian Gulf, Iran is ready to rebuild its energy industry. The West has been salivating since the July 2015 breakthrough on lifting the sanctions. At a conference in Tehran in late November, Oil Minister Bijan Namdar Zanganeh tantalized more than 300 foreign energy executives with 70 exploration and development projects up for bid, targeting $30 billion in new investments.

Ministry officials are promising better terms for foreign producers than found in Iran’s previous oil contracts, which allotted companies a fixed fee regardless of how much oil they produced and paid nothing to companies that spent more than was budgeted to develop a field. The new contracts will be valid for as long as 25 years, compared with seven before. Iran, which says it will disclose more details in February, wants to sign its first deal as soon as this spring.

“How often in one’s lifetime does a hydrocarbon superpower reopen for business?” says Ganesh Betanabhatla, a Houston-based private equity investor in oil and gas deals. As an American, he’s on a lonely quest to invest in exploration and production opportunities in Iran after sanctions are fully lifted, via plays by some of the midsize American oil producers he’s backed in the past. But just to talk to me about Iran, he had to insist his firm’s name not appear in this article. And as a big supporter of Jeb Bush and as national vice chairman of Maverick PAC, a fundraising group of wealthy Republicans younger than 40, Betanabhatla, 30, has endured taunts from GOP friends about his Iran pursuit. “This is a worthy cause,” he says, “but to me it comes at a cost.”

Betanabhatla’s bigger problem, he says, is that information on Iran’s vast hydrocarbon deposits is sketchy and scarce: “No one in the independent exploration and production world has set foot there in 36 years.” Hassanzadeh has helped Betanabhatla with research, and her network has arranged meetings for him with Iranian officials in New York and Europe. Her circle of sources includes a pair of thirtysomething white-shoe lawyers—among them Amir Ghavi at Willkie Farr & Gallagher in New York—as well as the CEO of a giant commodities trader in Switzerland and the head of development for one of Europe’s biggest oil producers.

Hassanzadeh became fascinated with energy while earning her bachelor’s degree in law at Islamic Azad University in Tehran under Hassan Sedigh, one of Iran’s leading oil and gas attorneys. She also interned in his law office, where she worked with executives at big oil companies from all over the world.

The experience eventually helped win her a scholarship from Royal Dutch Shell to pursue a master’s degree in law at the University of Cambridge in England in 2008 and 2009. “People are really intrigued by her, especially in the West,” says Jonathan Stern, Hassanzadeh’s dissertation adviser and the founder and chairman of the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies’ natural gas research program. “A young Iranian woman with great English skills, an academic background, real-world experience, and a law degree isn’t like anything anyone’s ever seen before.”

“I needed to break that boundary, to get into an arena where men have always been and continue to enforce their dominance”In terms of shock value, it’s not only that Hassanzadeh is a woman in the largely male world of oil and gas. It’s what she says. To her Iranian clients—CEOs her father’s age, desperate to nail down foreign partners after sanctions are lifted—Hassanzadeh tells them they’re not ready. Sure, well-connected Iranian companies can take small stakes in oil exploration and development deals, cede operational control to international oil companies, and sit back and collect dividends if the projects pay off. But Iran needs technology, know-how, and good jobs, and such things don’t come from these types of “semicolonial” relationships prevalent elsewhere in the Middle East, she says.

For Western companies to make joint ventures with Iranian partners on more equal terms, Iran must first build an “investment infrastructure” of independent auditors, lawyers, consultants, and courts that foreigners can trust, Hassanzadeh says. This takes time and a societal commitment to the rule of law. As of now, Iran doesn’t even have a reliable credit reference system.

“We’re trying to build this foundation,” she says. “We’re telling people, ‘Calm down, relax, there’s enough food for everyone. Don’t do anything now you’ll regret later.’?”

To potential Western investors, just as eager as Iranians to establish ties, she counsels patience. Her book, Iran’s Natural Gas Industry in the Post-Revolutionary Period—Optimism, Skepticism, and Potential, has a whole chapter on corruption and Iran’s need for legal reform. It was a hit with leaders at many of the big European oil companies that underwrite the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, according to the institute’s Howard Rogers, who spent 29 years with BP. The powerful research center is the locus of her influence outside Iran. After her book came out, she gained foreigners’ respect for having a clear-eyed view of Iran’s problems, and for not simply trying to earn a quick commission as a middleman. “Elham’s perspective is not one of unalloyed optimism,” Rogers says. “She has a realistic business sense of the challenges ahead.”

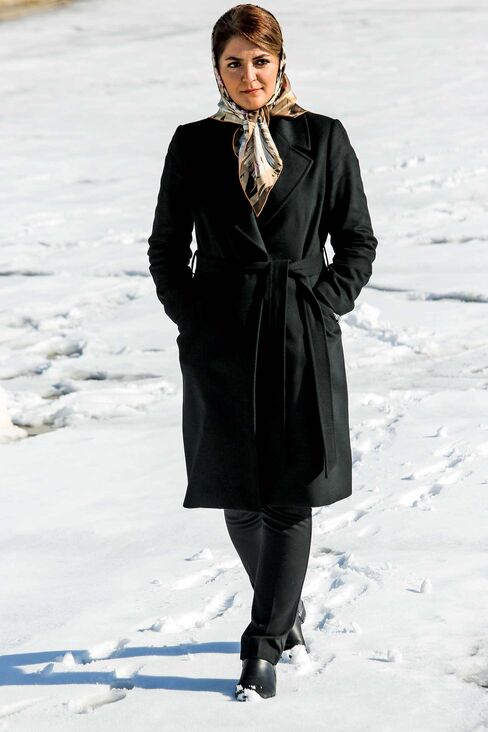

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="488"] Hassanzadeh at her office in Tehran. Photographer: Fatemeh Behboudi for Bloomberg Bussinessweek[/caption]

Hassanzadeh at her office in Tehran. Photographer: Fatemeh Behboudi for Bloomberg Bussinessweek[/caption]

While graybeards in turbans generate most of the headlines, it’s the young who are driving Iran’s reengagement with the West. Two-thirds of the nation’s 78 million people are under 35; almost 60 percent of high school graduates attend college, roughly the same rate as in Britain and France. The demand for jobs and a sense of normalcy by this educated demographic bulge is the gravest long-term threat to the Islamic regime—and its greatest human asset, Hassanzadeh says.

Zanganeh, the oil minister, a no-nonsense technocrat, has surrounded himself with relatively young staffers in their 20s and 30s. They’re linked to former professors, classmates, and friends throughout the vast Iranian diaspora.

Another point of tension: While women now make up more than 60 percent of the nation’s college students, they’re only 18 percent of its workforce. Education is cherished in Iran, but marriage and stay-at-home motherhood are pushed even harder, particularly by husbands. Hassanzadeh, who is single, says the worst discrimination she’s felt came from flirty senior executives at meetings “who think because you’re a woman you should be open” to their sexual advances. But they’re the exception, she says, with most oilmen going out of their way to be helpful. “It’s always like, ‘We can’t really believe a woman could get to your level of being so outspoken,’?” she says.

At a morning meeting in October at Namvaran, a large petroleum engineering company, Hassanzadeh and the director of business development, Parinaz Tahbaz, are treated to a rare event in the Middle East: The two female executives are served by a middle-aged office tea man. Tahbaz was one of four women to graduate with an engineering degree from Tehran University in 1996, along with 78 men. Now 70 percent of Iranian science graduates are women, she says. When she joined Namvaran the year she finished school, 2 out of 40 engineers in her department were women. Today the company is 45 percent female, and Tahbaz is the first woman among Namvaran’s five shareholders and members of the board. To earn the men’s trust, she had to work 14-hour days, spend long stretches on the road at job sites, and forget about having kids, she says. “My husband knows Namvaran is my first family.”

Hassanzadeh hasn’t decided if she’ll have a family. Iranian men aren’t interested in marrying women who are well-educated and financially independent, she says—“How are they supposed to control you?” Women either need to get married when they’re 17, “before you’re too intimidating,” or forget about their careers, she says. Hassanzadeh knew she wanted to get her Ph.D. before settling down. “I’ve been told if I meet a man I like, just don’t tell him what I do,” she says.

Hassanzadeh likes beating men at their own game. “I needed to break that boundary, to get into an arena where men have always been and continue to enforce their dominance,” she wrote in an e-mail. “I love the power/ecstasy/excitement which this sector offers me as a woman to fight head-to-head with men—that exact moment when you’ve not only crossed the boundaries, but have placed yourself ahead of men, that exact moment when you’re the only female panelist on a high-caliber panel of seven or eight men and they all remain silent and impressed by your insight.”

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="488"] Photographer: Fatemeh Behboudi for Bloomberg Bussinessweek[/caption]

Photographer: Fatemeh Behboudi for Bloomberg Bussinessweek[/caption]

When she first moved to Cambridge to earn her master’s degree, Hassanzadeh made fast friends with the American students—“the Brits kept boundaries,” she says. She visited the U.S. for the first and only time in December 2007. What was supposed to be a two-month trip, however, lasted only 10 days. Traveling alone through Washington Dulles International Airport, Hassanzadeh, then 23, was culled from a security line and directed into a secondary screening device called a puffer machine. The air blast lifted her shirt. Hassanzadeh panicked inside the glass chamber. A Transportation Security Administration supervisor, trying to calm her down, became overly friendly, she says. “That’s how you treat a young woman who has no idea what’s going on?” she asks. “You flirt with her?” She ended the trip after another verbal encounter with some horny male revelers on New Year’s Eve in Times Square. “I never wanted to go back to the States again,” she says.

After earning her master’s at Cambridge, Hassanzadeh, then 25, was appointed the youngest law lecturer ever at her alma mater in Tehran. At that point, conservative President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was at the height of his power, after he and Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei crushed the Green Revolution protesters in 2009 with baton-wielding militiamen and mass arrests of democratic activists. Hassanzadeh avoided discussing politics in the classroom, aware she was under special scrutiny for having lived in the West. She wouldn’t play favorites, either. She helped arrange an internship at the chamber of commerce for the studious son of a commander of the Basij, or Islamic militia. But she flunked the slacker son of another militant family, who then threatened to report her as a subversive to the university’s intelligence branch if she didn’t change his grade. She kicked him out of class and notified campus police.

An intelligence officer summoned Hassanzadeh for questioning. He said she’d been accused of speaking against the Islamic regime and presented her with a thick file on her travels the past five years. “Why’d you leave Iran so often?” he asked. She told him about her graduate studies and the abortive U.S. trip and turned over audio recordings of all her university lectures, which she’d assiduously taped for just such an inquiry. Her accuser was ultimately expelled. Hassanzadeh received a formal apology from the intelligence officer, expressing his fervent hope that she’d stay in Iran to continue serving the people.

She bolted for Oxford. “Ahmadinejad’s reelection was like a heart attack,” she says. “Everything collapsed, and everybody was suspecting each other. I said, ‘I’m leaving.’?”

The timing was perfect. When Hassanzadeh finished her energy dissertation in 2013, Rouhani was assuming the presidency. Fed up with “big-mouth” Iranians abroad who rant about the regime but won’t go home to help, Hassanzadeh returned to Tehran to start Energy Pioneers. Her co-founder, Nima Fateh, 44, had been a senior adviser to Mohammed Khatami, the reformist former president.

A lot of their work is assisting Iranian companies with preparing financial documents and feasibility studies that Western investors can trust and understand. The Saudi tensions haven’t hurt, so far. European companies continue reaching out for help, she says. Both sides remain bewildered. “They’re both speaking English, but from two different planets,” she says. Many of her Iranian clients, for example, assume that after sanctions they’ll be able to gain access to overseas funds for petroleum projects at roughly the same risk premium they paid before the Ahmadinejad tenure 15 years ago. Iran, after all, is a bastion of stability compared with the rest of the Middle East, they say. If the risk premium back then was 2 to 4, meaning Iranians could borrow money for projects at a benchmark interest rate plus 2 to 4 percentage points, “it’s now above 10,” Hassanzadeh says, citing a recent conversation with an investment banker in London. “I’m telling clients, ‘Guys, don’t be delusional!’?”

Hassanzadeh’s most advanced project is an enormous complex of natural gas refineries that’s planned to be the largest in the world. Located in the ancient port village of Siraf on the Persian Gulf, the project consists of eight interlinked refineries, to be built and owned by eight private companies with investments of $350 million each. The government is providing the gas from the South Pars field and pitching in about $1 billion of infrastructure. Three of the companies have hired Hassanzadeh to seek out foreign partners.

She wants to sign on more, which is what brings her to tea with Parinaz Tahbaz at Namvaran. The petroleum engineering company in Tehran is one of eight companies designated by the government to develop Siraf. As the cups are cleared away by the tea man, Hassanzadeh and Tahbaz commiserate about the need to rebuild Iran’s image. Hassanzadeh describes her “near panic” reading through one of her Siraf client’s feasibility studies before meeting prospective foreign investors. “They were incomplete, biased, and not professionally prepared,” she says.

Tahbaz says her company isn’t ready to hire outside experts for help yet. Namvaran first wants to narrow its list of potential foreign partners. American companies in particular are beginning to reach out to the company through third parties, expressing “even stronger interest than the others because this is an untouched market for them with huge opportunities,” Tahbaz says. “It may take some time, but people will understand that Iran is a country they can bank on.”

Hassanzadeh agrees, but says financing is more likely to come first from Japan, Korea, and China before Europe or the U.S. Still, she says that, in spite of her unhappy New Year in America, she knows how much Iranians love American technology and prefer U.S. goods over products from Europe and Japan. Within a few years, she says, even American oil producers will be back in Iran, where they’ll be welcomed with open arms. “They’ll get priority over everyone else.”

This article was written by Peter Waldman for Bloomberg Businessweek on Jan. 13, 2016.

QR code

QR code