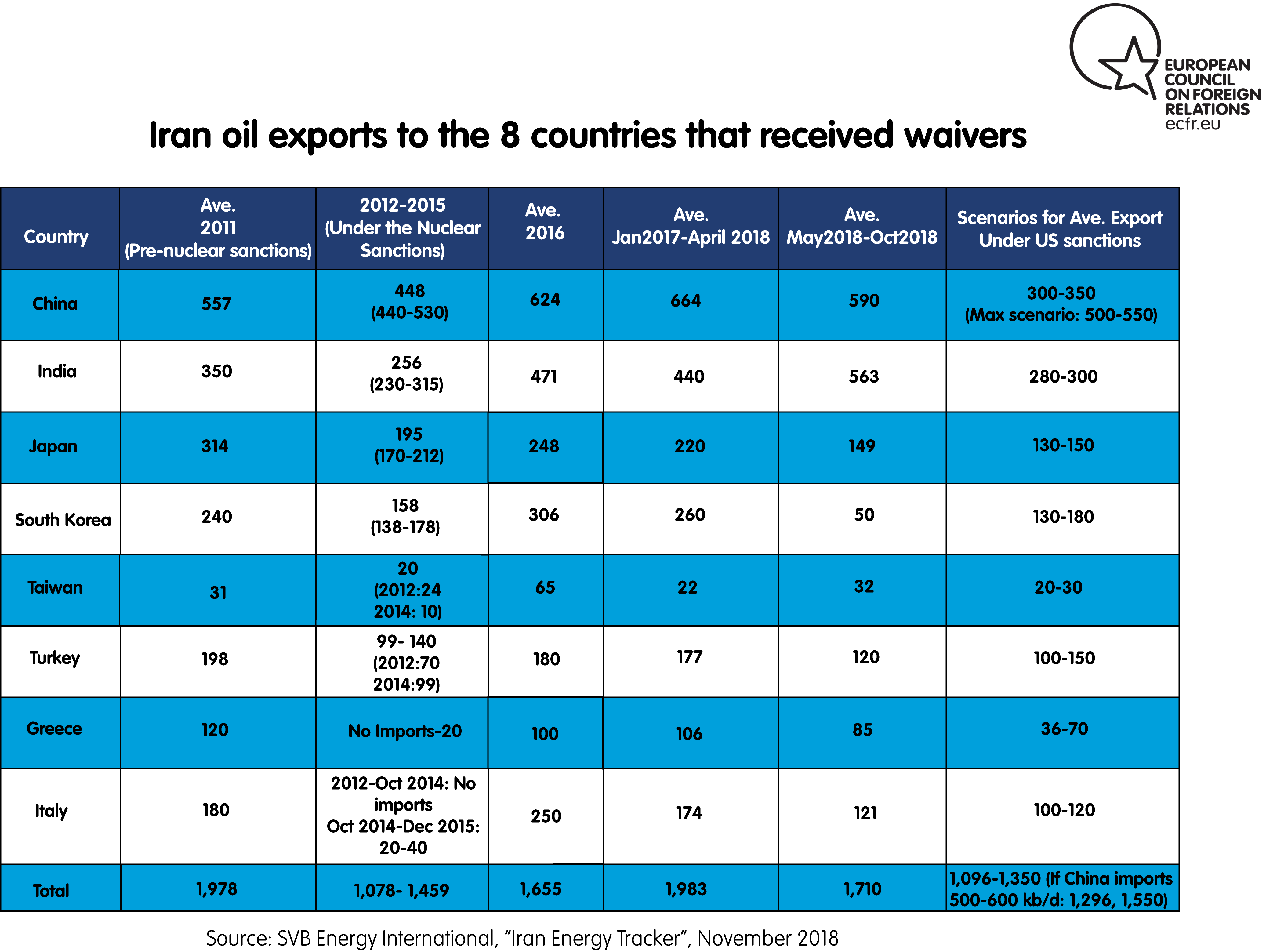

European Council on Foreign Relations |†Sara Vakhshouri: Iranís oil exports are likely to remain limited in 2019, with significant negative impact on Iranís economyLast month, the Trump administration reimposed sanctions on Iranís energy sector as part of its Ďmaximum pressureí campaign against Iran. But it nevertheless sought to prevent an unhelpful spike in oil prices ahead of the midterm elections. As a result the United States issued eight waivers to importers of Iranian oil: China, India, Japan, South Korea, Turkey, Taiwan, Italy, and Greece. The waivers allow these countries to import a limited amount of oil from Iran without falling foul of US sanctions.

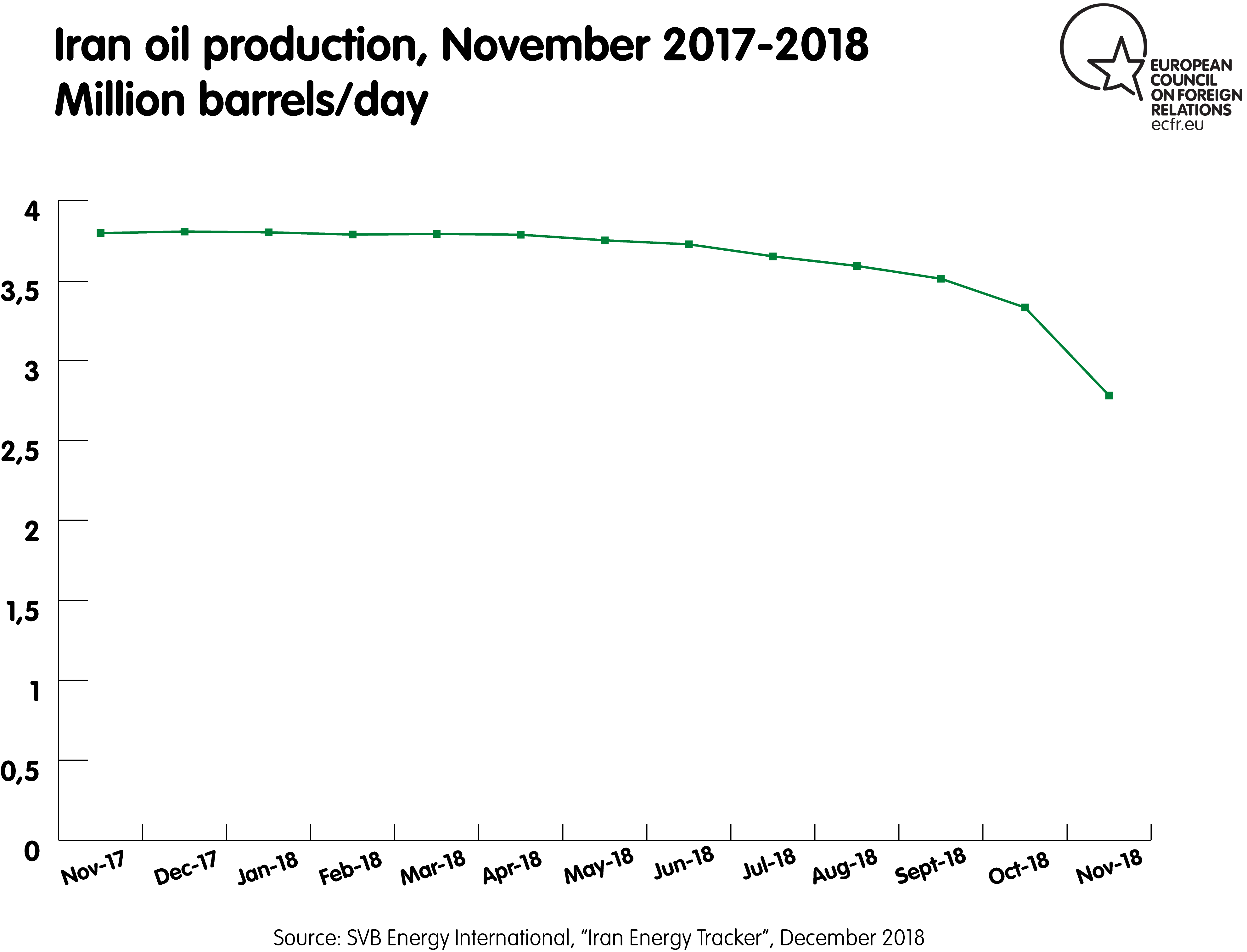

The Ďwaiver effectí was visible from the outset: oil prices dropped the day the waivers were announced. At the same time the market expected other oil producers Ė particularly Saudi Arabia and Russia Ė to cut back their temporary production, which had increased over the previous few months to cover Iranís drop in production. Saudi Arabia and Russia agreed to this at the 7 December OPEC meeting.

The waiver decision initially appeared to be a major setback for the US Ďzero oilí policy. Yet these eight waivers had a significant impact on the psychology and expectations of the oil market. They have created a perception that there will be an oversupply in the market in the short term, and at least through to the end of 2019.

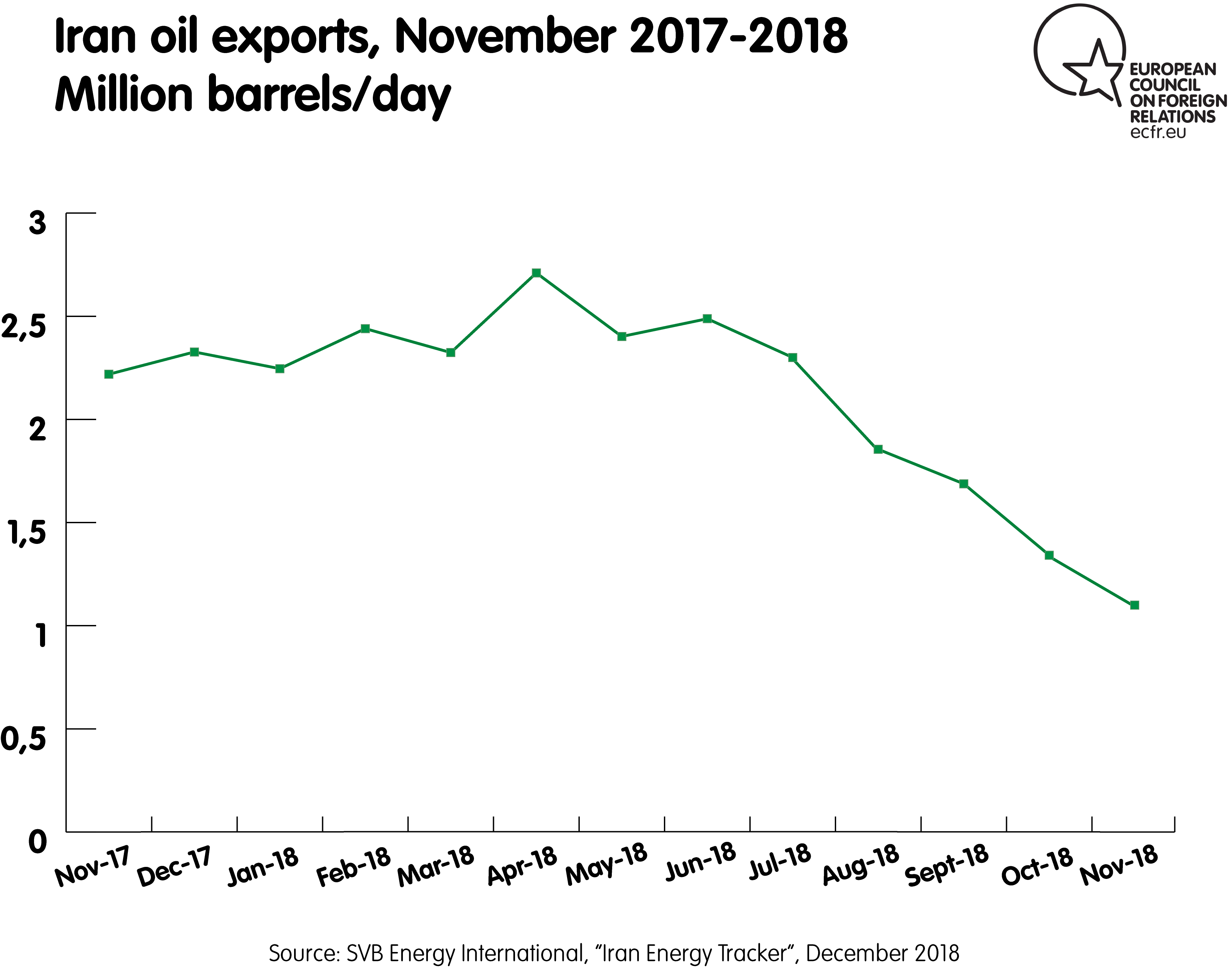

Now, weeks on from the granting of the waivers, no guidelines or details have been announced publicly with regard to how much these countries will be able to import. This has created confusion in the market as to how much Iran will produce up to April 2019, when the 180-day waiver issued for most of these countries is set to end. Upon the announcement of the waivers, many market analysts had anticipated that Iranís oil exports would increase to 1.5 million barrels per day (mb/d).

However, the reality could be more complicated. Iranís oil exports are actually unlikely to increase beyond 1.1 mb/d. At most, they could increase to 1.3 mb/d if market conditions are tight and there is not enough supply in the market. And if China decides to ramp its imports back up to 500,000-560,000 barrels per day (b/d) Iranís oil exports could increase even further, up to 1.5 mb/d.

Several factors prevent Iran oil exports from increasing significantly over the 180-day period.

China

Under the 2012-15 Obama-era nuclear sanctions, China imported roughly 440,000-530,000 b/d from Iran. However, in October 2018, in light of incoming US sanctions, its imports dropped to about 300,000 b/d. Chinese companies heavily invested in the US are worried and cautious about compliance with the sanctions. China National Petroleum Company Ė Iranís largest oil consumer in China Ė reportedly halted its imports in October and November in order to prevent any potential risk against its business and investment interests in the US. Even though the company†announced that it might resume imports†from Iran, the market does not expect imports to exceed more than 300,000-360,000 b/d. Adequate market supplies provided by Saudi Arabiaís and Russiaís production mean the Chinese are disinclined to import more Ďproblematicí Iranian oil.

Besides US sanctions exposure for Chinese companies, the ongoing trade negotiations with the US are likely to influence Chinaís decisions. The US government is granting Ė on a case-by-case basis Ė waivers on export tariffs to Chinese companies for their trade with, and exports to, the US. It is likely that major companies and the Chinese government are exercising caution with their oil imports from Iran to avoid other sources of tension with Washington. CNPC has also recently suspended its investment in Iranís South Pars giant gas field in order to minimise tensions over the trade negotiations. It is noteworthy that Saudi Aramco recently singed five new crude oil supply contracts with China to supply its new refinery capacity in 2019. This will significantly increase Saudi Arabiaís market share in China, reaching a total of about 1.6 mb/d. Saudi Arabia exported an average of about 1 mb/d of oil to China in first 10 months of 2018. This will increase Saudi Arabiaís market share in China by about 11 percent on 2017.

Simply put, China is using its Iran oil imports as part of its tariff negotiations with the US. This is spilling over into Chinaís own negotiations with Iran. Knowing Iranís limitations for export,†Bejing is bargaining hard and strong with Tehran†over prices and delivery conditions. China was very late to issue oil purchase orders to National Iranian Oil Company for the month of November. Chinese refineries waited late Ė the third week of October Ė to submit their purchase orders to Iranian authorities.

Limited shipping capacity and payment issues

Iranís oil exports have dropped significantly since August 2018 following the implementation of the first round of US secondary sanctions. These put strict limitations on Iranís oil insurance and shipping. Most of the oil shipped since then has gone through the National Iranian Tanker Company (NITC), even oil shipments to China. Lack of access to adequate insurance has increased the risk of shipping. Most tanker owners are either unwilling to rent their tankers for shipping Iranian oil cargoes or are demanding very high leasing premiums. Hence, importers are mostly relying on NITC to deliver their oil cargoes. This has also impacted on Iranís refined petroleum products and petrochemical export.

Historically, and in the months since August, NITCís oil shipments stood at between only 1-1.1 mb/d; this too will prevent Iran from increasing its exports. This is especially the case for Iranís allocated shipping export capacity to the European Union countries holding waivers (Italy and Greece), as most of its domestic shipping capacity is busy delivering oil to its customers in Asia. Meanwhile, like China, European countries will remain wary of the risks of importing Iranian oil even with the waivers in place.

Sanctions limit Iranís access to its oil income in the form of cash and hard currency. Due to the latest US sanctions, importers of Iranian oil have to keep Iranís oil revenues in an escrow account, and Iran can use this credit to purchase certain goods or services. Even for these clients, payment restrictions could also keep oil purchases lower than Tehran hopes. China, India, and Turkey have diverse trade relations with Iran and in theory could pay for Iranian oil with goods such as food and medicine. However, for countries such as Japan and South Korea, paying back Iranís oil money is complicated. In the case of South Korea, Iran recently signed a food-for-oil agreement. However, there are limitations in terms of volumes and diversity of Iranís required food from each particular country. Iran has not signed any similar contracts with Japan yet. Auto and electronics industry owners in Asian countries are highly hesitant to barter their products with Iranian oil money, again because they fear losing one of their largest markets: the US.

OPEC

The uncertainty over Iranís oil exports created a difficult decision-making environment for OPEC members and their non-OPEC allies during their 7 December meeting to finalise a decision over production cuts. This decision aimed to maintain market balance. OPEC and Russia finally agreed to cut their production by 1.2 m/bd, of which OPEC will cut 800,000 b/d and non-OPEC countries (mostly Russia) will cut about 400,000b/d. This volume is in line with Iranís oil exports of 1.1-1.3mb/d until the end of the 180-day period. Russian and Saudi Arabian oil production had increased to historic highs in the past few months.

Saudi Arabia in particular came under pressure to reduce its production and generate higher prices, to in turn maintain domestic budget balances. Given the recent warm political, energy, and investment ties between Russia and Saudi Arabia, Russia supported Saudi Arabiaís target for higher oil prices. If not Saudi Arabiaís oil price target of $70/b, Russia is supporting at least price range of around $60-65/b. Russia also agreed to join OPEC members in a further production cut.

Another significant outcome of this meeting was that Iran was excluded from any production or export cut as its production and export is already below its usual capacity due to the sanctions. In November, Iranian crude oil exports fell slightly below 3 mb/d. The sanctions have not only had a significant impact on Iran crude oil exports, but they have also had a negative impact on Iranís petroleum product exports. This means that some Iranian refineries are unable to run at full capacity given their export limitations.

A variety of factors are set to impact on the oil market and Iranian oil exports. If the market is adequately supplied and prices remain relatively low, even importers that have received waivers will have little incentive to import oil from Iran. With the prospects of US export capacity rising in 2019 and Saudi Arabiaís and Russiaís own considerable export capacity, Iranian oil exports of 1.1-1.3 mb/d or even less may ensue. If prices remain low countries with waivers may still choose not to import oil from Iran even up to the level for which they received the waivers. Taiwan, Italy, Greece, Turkey, and Japan might behave in this way if they are not convinced that the economic profit of importing Iranian oil is not greater than the risks related to shipping and insuring Iranian oil cargoes. Iranís oil exports are likely to remain limited in 2019, and so the countryís annual budget for 2019 is based on an export of 1.5 mb/d. This could have a significant negative impact on Iranís economy Ė particularly if oil prices remain relatively low throughout 2019.

†Sara Vakhshouri is the founder and president of SVB Energy International.

QR code

QR code