By the standards of democratic countries, presidential elections in Iran are neither free nor fair; but the range of candidates does offer an element of choice. Whether voters will go for this narrow field is another matter.

By the standards of democratic countries, presidential elections in Iran are neither free nor fair; but the range of candidates does offer an element of choice. Whether voters will go for this narrow field is another matter.The election authority has allowed eight people to stand in the ballot on 14 June. Five belong to the conservative camp, one is a centrist and the other is a reformist. The last one, an independent, is not being taken seriously.

The choice of the contenders suggests that the conservatives and their right-wing supporters, particularly those in the Revolutionary Guards, are setting the election agenda and seem to have the upper hand.

During the past few months, their view of political events has been the most accurate in foreseeing developments and articulating group interests accordingly.

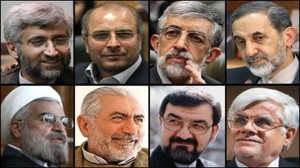

The candidates are:

- Nuclear strategist Saeed Jalili - conservative

- Tehran mayor Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf - conservative

- Former Majlis Speaker Gholamali Haddad Adel - conservative

- Advisor to the Supreme Leader Ali Akbar Velayati - conservative

- Former Revolutionary Guards commander Mohsen Rezaie - conservative

- Former nuclear negotiator Hasan Rouhani - centrist

- Former Vice President Mohammad Reza Aref - reformist

- Mohammad Gharazi - independent

Public opinion

At this stage it is difficult to predict how people might vote or whether they sill vote at all.

In the last election in 2009 more than over 80% of Iranian voters took part. But now that senior reformist leaders are under house arrest and former presidents Mohammad Khatami and Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani have not been allowed to stand, some reformist supporters might decide not to vote.

The conservative vote is also unpredictable because their camp is split between the supporters and opponents of President Mahmud Ahmadinejad and this could break up their votes.

The role of the undecided "floating" voter, who is not loyal to any of the camps, is critical for all sides.

Conservatives

The conservatives are still playing a game of camouflage by fielding five candidates. This protects their final candidate from attacks from rivals and public criticism.

The two main figures in the camp are Mr Jalili and Mr Qalibaf. Mr Qalibaf represents mainstream conservative thinking, while Mr Jalili is further to the right and has worked closely with the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei .

The critical factor is how the conservative leadership will swing its vote at the final stage. That decision will put their bloc vote - mobilized noticeably by the para-military and the Revolutionary Guards - behind the final chosen contender.

Centrists and reformists

Following the disqualification of former President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, the reformist and centre factions are in a weak position. Their two candidates are not their first choice.

Mr Rouhani, a centrist, is a former nuclear negotiator with the aura of a cautious diplomat. Mr Aref, the reformist, worked behind the scenes when he was a vice president and is seen as a quiet operator.

Neither is charismatic enough to turn the tide through sheer campaigning.

Furthermore, their support organizations have been shut down, their activists harassed and the publications that back them restricted.

If Mr Aref and Mr Rouhani both stand they will have to compete for the same voters and may thus cancel each other out.

Safe option

The conservative-controlled political establishment has played safe by eliminating candidates who could have created an unpredictable situation.

If they had allowed Mr Rafsanjani to enter the race, there would have been the risk of massive mobilizations on the streets. This happened in the 2009 elections and the regime is determined not to allow a repeat.

Although the police and security forces have detailed plans for dealing with possible unrest, a preventative approach was favoured. Better safe than sorry.

Future

If the disqualified candidates are not reinstated, a conservative victory seems highly likely. Both Mr Jalili and Mr Qalibaf have a good chance of becoming the next president. An editorial in a leading conservative newspaper speculated that Mr Jalili has the better chance.

The future for the reformist and the centrist factions is uncertain. The establishment conservatives want to maintain them, but only as small groups on the political fringes and under firm control.

But if the process of eliminating dissidents and critics becomes prevalent, the regime could seriously undermine its social base and consequently become more dependent on coercive methods to maintain order.

By BBC

The Iran Project is not responsible for the content of quoted articles.