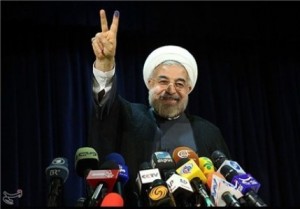

One of the most important questions in the Middle East this year is whether Hassan Rouhani's election will mark a new era -- both for Iranians and the outside world. The answer could mean the difference between peace and yet another war. Rouhani's campaign certainly made lots of promises. One of his most striking posters was a bright blue textograph of his face crafted from a slogan promising "a government of good sense and hope." The Scottish-educated cleric energized an election many Iranians had considered boycotting after pledging that "freedoms should be protected." He also won over key youth and female votes by vowing in televised debates to "minimize government interference" in culture and society and to give women "equal rights and equal pay."

One of the most important questions in the Middle East this year is whether Hassan Rouhani's election will mark a new era -- both for Iranians and the outside world. The answer could mean the difference between peace and yet another war. Rouhani's campaign certainly made lots of promises. One of his most striking posters was a bright blue textograph of his face crafted from a slogan promising "a government of good sense and hope." The Scottish-educated cleric energized an election many Iranians had considered boycotting after pledging that "freedoms should be protected." He also won over key youth and female votes by vowing in televised debates to "minimize government interference" in culture and society and to give women "equal rights and equal pay."The upbeat promises have continued apace since the June 14 election, particularly on Rouhani's two English and Farsi Twitter accounts. "This victory was a victory of wisdom,�#moderation, progress, awareness, commitment and religiosity over extremism & bad behavior," @hassanrouhani tweeted on June 15. The "bad behavior" was clearly a dig at outgoing President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, whose status has plummeted over the past year. He leaves office almost in disgrace.

Online, Rouhani even discreetly tipped his turban to the Great Satan. Four days after the vote, his account tweeted a decade-old picture of Rouhani visiting a U.S. field hospital set up after the devastating 2003 earthquake in historic Bam. He is pictured next to an American female medic.

Now Iran's new president has to deliver. After the Aug. 4 inauguration, Rouhani faces a grueling test of the popularity he won at the polls against five other candidates. Iran's economy is toxic. Political divisions border on schisms. Regional allies--both secular and Islamist--are literally under fire. And the outside world has threatened military action if Tehran does not compromise on its nuclear program. Rouhani will find few quick fixes either. His gentle smile will only get him so far.

***

"It's the economy stupid" applies as much in the Islamic Republic as in any capitalist society. Rouhani inherits an almost existential challenge in putting out the financial fires. The economic situation is beyond grim due to a combination of punishing international sanctions and Ahmadinejad's gross mismanagement.

Iran's currency has lost about half its value since mid-2012. At least one out of four young people is now unemployed--including 4 million university graduates--in a country where more than half the voters are under 35. The Central Bank put inflation at 36 percent this spring, but Rouhani said his incoming team estimated that it was closer to 42 percent. Disgruntlement is visible. Sporadic demonstrations, including a July rally by steelworkers outside parliament, have protested unpaid salaries and layoffs.

Iran's economic lifeline is oil. But crude oil exports were cut by almost 40 percent in 2012--to 1.5 million barrels per day, the lowest in more than a quarter century, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. By July 2013, the World Bank reported that Tehran had not paid back loans totaling $79 million for more than six months (out of $679 million due overall), which also meant Tehran would be ineligible for new funding and would find it harder to get new money from commercial creditors.

"For the first time since the imposed war [with Iraq from 1980 to 1988], our economic growth has been negative for two years in a row. And this is the first time that negative growth is accompanied by high inflation -- the highest inflation in the region or perhaps in the world," Rouhani told the country's parliament in July. In Iran's unusual political system, the president's biggest portfolio is the economy--and it could make or break his presidency.

***

During the presidential debates, Rouhani was quite conciliatory toward the outside world, at least compared with the defiant and discordant Ahmadinejad. "We need to move away from extremism," Rouhani said on national television. "We should maintain the country's interests and national security to provide conditions where we create opportunities." The key, of course, will be whether Iran and the outside world can settle longstanding questions about Iran's nuclear program.

Unlike the economy, Rouhani is uniquely qualified on this issue. He is a mid-ranking cleric, but he was also the national security adviser for 16 years. As chief nuclear negotiator, he brokered a rare deal with the West in 2003-4, when Iran temporarily suspected uranium enrichment, a fuel process that can be used for both peaceful nuclear energy and the world's deadliest weapon. He left the job shortly after Ahmadinejad took office in 2005.

Rouhani actually took a potshot at Ahmadinejad's team--including Saeed Jalili, the chief nuclear negotiator and another presidential candidate--in the campaign this summer. Among the six major powers negotiating with Iran, Jalili was famed for his long-winded tirades and stalling tactics that went nowhere during the five rounds of diplomacy since April 2012. The joke in Washington was that U.S. officials would actually not have minded if Jalili won the election, because at least they would no longer have to sit across from him at the negotiating table. He may have had the same reputation in Tehran.

"The nuclear issue will only be resolved through real negotiations, not just announcements," Rouhani said during the debates. "Iran's foreign policy should be placed in the hands of skilled, experienced people -- not people who do not know what they are talking about."

The sixth round of negotiations--with the United States, Britain, China, France, Germany and Russia--is expected to resume this fall. "Iran will be more transparent to show that its activities fall within the framework of international rules." Rouhani said in his first press conference after the election. The International Atomic Energy Agency--the U.N. nuclear watchdog--particularly wants access to facilities and scientists so far off-limits to the outside world. The looming question is also whether the regime will finally agree to direct talks with the United States to expedite resolution.

"Relations between Iran and the United States are a complicated and difficult issue. It's nothing easy," Rouhani said at his first press conference. "This is a very old wound that is there, and we need to think about how to heal this injury. We don't want to see more tension. Wisdom tells us both countries need to think more about the future and try to sit down and find solutions to past issues and rectify things."

Rouhani knows the nuclear program intimately. He also knows that a deal that lessens or eliminates sanctions would in turn be the key to reversing Iran's rapid economic decline. "It is very good for [nuclear] centrifuges to spin," he said in the final debate on foreign policy. "But it's also good for the lives of people to spin." For all his realism, however, Iran's new president remains committed to the unique ideology of the world's only modern theocracy. He also opposed terms of a deal offered in 2009.

***

The central challenge for Rouhani is that he will not have the last word on virtually anything. In Iran's hybrid political system, a cleric is the ultimate executive. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has virtual veto power, sometimes in subtle ways, over everything from cabinet appointments to political agendas and foreign policy. The last three presidents ended up alienating the supreme leader--and losing influence for themselves and their political factions.

Tehran also has rival power centers. To win support for his initiatives, Rouhani will need to be a master wrangler to keep Iran's herd of bull-headed politicians in the same corral. He will have to navigate a balance between hardline principlists (so called for their rigid revolutionary principles) at one end of the spectrum and reform sentiments at the other, with many political shades between the two poles. For all their differences, Iranian and American politics actually have something in common--intense government rivalries that produce gridlock.

After the election, Rouhani told a packed press conference that his government would include "moderates, principlists and reformists. There will be no restrictions. I don't like the word coalition, it will go beyond factions and be based on meritocracy."

But blocks have already formed to hold Rouhani in check. Iran's unicameral parliament -- the Majlis -- is dominated by conservatives and hardliners, while Rouhani is a centrist. In a recent letter, 80 principlist members of parliament warned against naming "seditionists," a reference to reformers. Their six-point demands included absolute commitment by any appointee to revolutionary principles in domestic and foreign policies and total obedience to the supreme leader.

Iran's elite Revolutionary Guards also wield enormous political influence. Under Ahmadinejad, veterans from the 1980-88 war with Iraq strengthened their hold on top government jobs, both nationally and in the provinces. The Revolutionary Guards also are a dominant economic force, holding billions of dollars in government contracts having little or nothing to do with the military. They are not shy when it comes to getting their way.

So the honeymoon may be brief for Rouhani. Like his Western counterparts, he probably has 18 months to two years to produce something tangible before risking the leverage gained by his surprising first-round victory. Then he will have to begin thinking about the next election cycle.

By The Atlantic

The Iran Project is not responsible for the content of quoted articles.