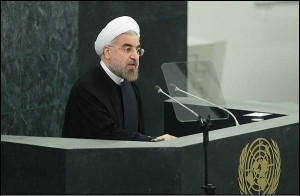

President Hassan Rouhani generated a positive buzz yesterday with his�United Nations�General Assembly statements about Iran's determination to resolve the nuclear impasse with the international community. Though he argued Tehran was not prepared to give up its enrichment program, the new president declared "nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass destruction have no place in Iran's security," adding that his government was now committed to "time-bound and result-oriented talks to build mutual confidence and removal of mutual uncertainties with full transparency" to resolve any doubts.

President Hassan Rouhani generated a positive buzz yesterday with his�United Nations�General Assembly statements about Iran's determination to resolve the nuclear impasse with the international community. Though he argued Tehran was not prepared to give up its enrichment program, the new president declared "nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass destruction have no place in Iran's security," adding that his government was now committed to "time-bound and result-oriented talks to build mutual confidence and removal of mutual uncertainties with full transparency" to resolve any doubts.While this lays the basis for the resumption of negotiations with the United States and its allies, we need not await the results to test Rouhani's sincerity. That can begin Friday, September 27, when Iranian and International Atomic Energy Agency officials sit down in Vienna in a long-scheduled meeting to break the protracted deadlock over unanswered questions about the breadth of Tehran's nuclear enterprise.

Director General Yukiya Amano summed up the stakes in his September 9 statement to the IAEA's board of governors: "The agency has not been able to begin substantive work with�Iran�on resolving outstanding issues, including those related to possible military dimensions on Iran's nuclear programme." The Vienna talks now provide the best opportunity to make progress.

The discussions will mark the 11th time since January 2012 that the agency and�Iran�have met to develop a "structured approach" to resolve open questions.

It comes with a dash of hope from Rouhani's past. From 2003 to 2005, he was Iran's nuclear negotiator. His tenure came just when Tehran had fallen to multiple faux pas following the August 2002 revelation by an Iranian dissident that the revolutionary regime had built a secret nuclear enrichment plant at Natanz.

Iran's first response claimed victimhood, due to "selective and discriminatory" diplomacy, "false attribution" and "partisan politics." When that approach failed to garner sympathy, Tehran arranged for then-IAEA Director General Mohamed ElBaradei to visit Natanz. But that backfired when IAEA requested � and got � grudging access to other activities�Iran�denied being involved in.

It fell on Rouhani, as nuclear negotiator, to pick up the pieces. He pursued three tracks. One came in Iran's declaration to IAEA that it was "commencing a new phase of confidence and co-operation" by volunteering new nuclear information. As a sign of good faith, Tehran signed (but did not ratify) the Additional Protocol that would allow IAEA to visit undeclared nuclear sites.

The second emerged in a letter Rouhani wrote to the Bush administration, calling for dialogue to address all issues between Washington and Tehran. (The White House ignored the communication.) Then, most significantly, Rouhani entered into negotiations with British, French and German diplomats with ElBaradei at times acting as interlocutor.

These negotiations, which resulted in Iran's suspension of enrichment activities, marked perhaps the closest the nuclear impasse has ever come to a solution. However, the talks stalled due to a combination of continuing evidence that supported Western suspicions about Iran's nuclear cheating; a trickle of what Tehran viewed as inconsequential incentives from the Europeans, and pressure from elements in the Iranian government calling for preservation of enrichment capacity.

Then the ascendancy of the conservative Ahmadinejad presidency in August 2005 ended Rouhani's efforts and returned Iran to a more contentious posture.

Since Rouhani is now in a key policy position, with the Supreme Leader's blessing, this is the time to test Iran's seriousness. The Vienna meeting is the place to start.

Success will require the new government to respond to a series of issues IAEA outlined in 2011. These include information about the "relevant locations, equipment or documentation related to possible military dimensions to Iran's nuclear programme." Tehran must also provide information about uranium conversion and metallurgy, nuclear-relevant high explosives manufacturing, and testing of missile re-entry vehicle designs for nuclear payloads, among many other matters.

Iran informed the IAEA earlier this month that it is prepared to cooperate in "mutual confidence-building and constructive interaction" in order to "put an end to Iran's nuclear dossier." On Friday, it will have the opportunity to do just that by agreeing to the structured approach the agency proposes.

Should Tehran waiver or fail to cooperate, it will have to bear the consequences of continued international sanctions � and the risk that "all other options" will follow as well.

By Reuters

The Iran Project is not responsible for the content of quoted articles.